Gia

Đình Mũ Đỏ Việt Nam

Vùng Thủ đô Hoa Thịnh Đốn và Phụ cận

Ngược dòng Thời gian

Chủ đề: Mậu Thân 1968

Tác giả: Douglas Pike

50

năm tưởng niệm Tết Mậu Thân

Học giả Douglas Pike đã nhận định

Hue Massacre, Tet 1968

(The Vietcong

Strategy of Terror, by Douglas Pike)

(In Memory of the 7,600

civilians murdered in Hue by Vietnamese communists)

Bài 10

Bấm vào đây để in ra giấy (Print)

The city of Hue is one of the saddest cities of our earth, not

simply because of what happened there in February 1968,

unthinkable as that was. It is a silent rebuke to all of us,

inheritors of 40 centuries of civilization, who in our century

have allowed collectivist politics–abstractions all–to corrupt us

into the worst of the modern sins, indifference to inhumanity.

What happened in Hue should give pause to every remaining

civilized person on this planet. It should be inscribed, so as

not to be forgotten, along with the record of other terrible

visitations of man’s inhumanity to man which stud the history of

the human race. Hue is another demonstration of what man can

bring himself to do when he fixes no limits on political action

and pursues incautiously the dream of social perfectibility.

What happened in Hue, physically, can

be described with a few quick statistics. A Communist force which

eventually reached 12,000 invaded the city the night of the new

moon marking the new lunar year, January 30, 1968. It stayed for

26 days and then was driven out by military action. In the wake

of this Tet offensive, 5,800 Hue civilians were dead or missing.

It is now known that most of them are dead. The bodies of most

have since been found in single and mass graves throughout Thua

Thien Province which surrounds this cultural capital of Vietnam.

Such are the skeletal facts, the

important statistics. Such is what the incurious word knows any

thing at all about Hue, for this is what was written, modestly by

the word’s press. Apparently it made no impact on the world’s

mind or conscience. For there was no agonized outcry. No

demonstration at North Vietnamese embassies around the world. In

a tone beyond bitterness, the people there will tell you that the

world does not know what happened in Hue or, if it does, does not

care.

The Battle

The Battle of Hue was part of the

Communist Winter–Spring campaign of 1967–68. The entire campaign

was divided into three phases: Phase I came in October, November,

and December of 1967 and entailed “coordinated fighting methods,”

that is, fairly large, set–piece battles against important fixed

installations or allied concentrations. The battles of Loc Ninh

in Binh Long Province, Dak To in Kontum Province, and Con Tien in

Quang Tri Province, all three in the mountainous interior of

South Vietnam near the Cambodian and Lao borders, were typical

and, in fact, major elements in Phase I.

The entire campaign

was divided into three phases: Phase I came in October, November,

and December of 1967 and entailed “coordinated fighting methods,”

that is, fairly large, set–piece battles against important fixed

installations or allied concentrations. The battles of Loc Ninh

in Binh Long Province, Dak To in Kontum Province, and Con Tien in

Quang Tri Province, all three in the mountainous interior of

South Vietnam near the Cambodian and Lao borders, were typical

and, in fact, major elements in Phase I.

Phase II came in January, February, and

March of 1968 and involved great use of “independent fighting

methods,” that is, large numbers of attacks by fairly small

units, simultaneously, over a vast geographic area and using the

most refined and advanced techniques of guerrilla war. Whereas

Phase I was fought chiefly with North Vietnamese Regular (PAVN)

troops (at that time some 55,000 were in the South), Phase II was

fought mainly with Southern Communist (PLAF) troops. The

crescendo of Phase II was the Tet offensive in which 70,000

troops attacked 32 of South Vietnam’s largest population centres,

including the city of Hue.

Phase III, in April, May, and June of

1968, originally was to have combined the independent and

coordinated fighting methods, culminating in a great fixed battle

somewhere. This was what captured documents guardedly referred to

as the “second wave”. Possibly it was to have been Khe Sanh, the

U.S. Marine base in the far northern corner of South Vietnam. Or

perhaps it was to have been Hue. There was no second wave chiefly

because events in Phases I and II did not develop as expected.

Still, the war reached its bloodiest tempo in eight years then,

during the period from the Battle of Hue in February until the

lifting of the siege of Khe Sanh in late summer.

independent and

coordinated fighting methods, culminating in a great fixed battle

somewhere. This was what captured documents guardedly referred to

as the “second wave”. Possibly it was to have been Khe Sanh, the

U.S. Marine base in the far northern corner of South Vietnam. Or

perhaps it was to have been Hue. There was no second wave chiefly

because events in Phases I and II did not develop as expected.

Still, the war reached its bloodiest tempo in eight years then,

during the period from the Battle of Hue in February until the

lifting of the siege of Khe Sanh in late summer.

American losses during those three

months averaged nearly 500 killed per week; the South Vietnamese

(GVN) losses were double that rate; and the PAVN–PLAF losses were

nearly eight times the American loss rate. In the Winter–Spring

Campaign, the Communists began with about 195,000 PLAF main force

and PAVN troops. During the nine months they lost (killed or

permanently disabled) about 85,000 men.

The Winter–Spring Campaign was an

all–out Communist bid to break the back of the South Vietnamese

armed forces and drive the government, along with the Allied

forces, into defensive city enclaves. Strictly speaking, the

Battle of Hue was part of Phase I rather than Phase II since it

employed “co–ordinated fighting methods” and involved North

Vietnamese troops rather than southern guerrillas. It was fought,

on the Communist side, largely by two veteran North Vietnamese

army divisions: The Fifth 324–B, augmented by main forces

battalions and some guerrilla units along with some 150 local

civilian commissars and cadres.

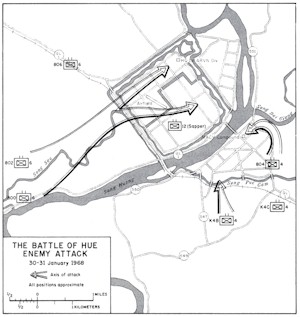

Briefly the Battle of Hue consisted of

these major developments: The initial Communist assault, chiefly

by the 800th and 802nd battalions, had the force and momentum to

carry it across Hue. By dawn of the first day the Communists

controlled all the city except the headquarters of the First ARVN

Division and the compound housing American military advisors. The

Vietnamese and Americans moved up reinforcements with orders to

reach the two holdouts and strengthen them. The Communists moved

up another battalion, the 804th, with orders to intercept the

reinforcement forces. This failed, the two points were reinforced

and never again seriously threatened.

The battle then took on the aspects of

a siege. The Communists were in the Citadel and on the western

edge of the city. The Vietnamese and Americans on the other three

sides, including that portion of Hue south of the river,

determined to drive them out, hoping initially to do so with

artillery fire and air strikes. But the Citadel was well built

and soon it became apparent that if the Communists’ orders were

to hold, they could be expelled only by city warfare, fighting

house by house and block by block, a slow and costly form of

combat. The order was given.

By the third week of February the

encirclement of the Citadel was well under way and Vietnamese

troops and American Marines were advancing yard by yard through

the Citadel. On the morning of February 24, Vietnamese First

Division soldiers tore down the Communist flag that had flown for

24 days over the outer wall and hoisted their own. The battle was

won, although sporadic fighting would continue outside the city.

Some 2,500 Communists died during the battle and another 2,500

would die as Communists elements were pursued beyond Hue. Allied

dead were set at 357.

The Finds

In the chaos that existed following the

battle, the first order of civilian business was emergency

relief, in the form of food shipments, prevention of epidemics,

emergency medical care, etc. Then came the home rebuilding

effort. Only later did Hue begin to tabulate its casualties. No

true post–attack census has yet been taken. In March local

officials reported that 1,900 civilians were hospitalized with

war wounds and they estimated that some 5,800 persons were

unaccounted for.

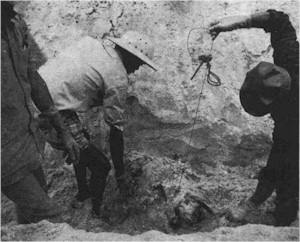

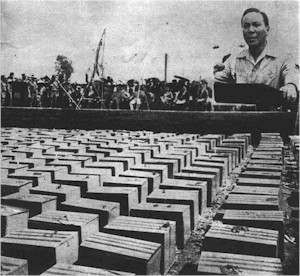

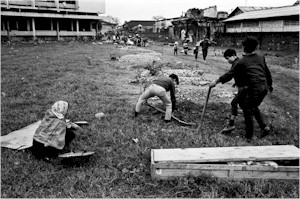

The first discovery of Communist

victims came in the Gia Hoi High School yard, on February 26 ;

eventually 170 bodies were recovered.

In the next few months 18 additional

grave sites were found, the largest of which were Tang Quang Tu

Pagoda (67 victims), Bai Dau (77), Cho Thong area (an estimated

100), the imperial tombs area (201), Thien Ham (approximately

200), and Dong Gi (approximately 100). In all, almost 1,200

bodies were found in hastily dug, poorly concealed graves.

were Tang Quang Tu

Pagoda (67 victims), Bai Dau (77), Cho Thong area (an estimated

100), the imperial tombs area (201), Thien Ham (approximately

200), and Dong Gi (approximately 100). In all, almost 1,200

bodies were found in hastily dug, poorly concealed graves.

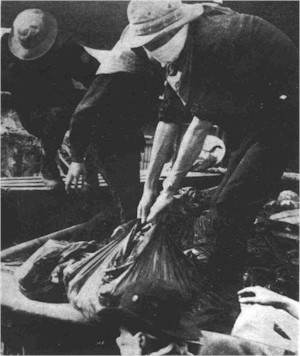

At least half of these showed clear

evidence of atrocity killings: hands wired behind backs, rags

stuffed in mouths, bodies contorted but without wounds

(indicating burial alive). The other nearly 600 bore wound marks

but there was no way of determining whether they died by firing

squad or incidental to the battle.

The second major group of finds was

discovered in the first seven months of 1969 in Phu Thu

district–the Sand Dune Finds and Le Xa Tay–and Huong Thuy

district–Xuan Hoa–Van Duong–in late March and April. Additional

grave sites were found in Vinh Loc district in May and in Nam Hoa

district in July. The largest of this group were the Sand Dune

Finds in the three sites of Vinh Luu, Le Xa Dong and Xuan 0

located in rolling, grasstufted sand dune country near the South

China Sea. Separated by salt–marsh valleys, these dunes were

ideal for graves. Over 800 bodies were uncovered in the dunes.

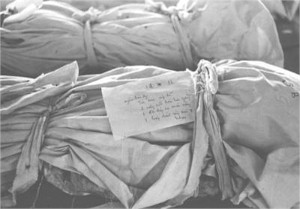

In the Sand Dune Find, the pattern had

been to tie victims together in groups of 10 or 20, line them up

in front of a trench dug by local corvee labour and cut them down

with submachine gun (a favourite local souvenir is a spent

Russian machine gun shell taken from a grave). Frequently the

dead were buried in layers of three and four, which makes

identification particularly difficult.

or 20, line them up

in front of a trench dug by local corvee labour and cut them down

with submachine gun (a favourite local souvenir is a spent

Russian machine gun shell taken from a grave). Frequently the

dead were buried in layers of three and four, which makes

identification particularly difficult.

In Nam Hoa district came the third, or

Da Mai Creek Find, which also has been called the Phu Cam death

march, made on September 19, 1969. Three Communist defectors told

intelligence officers of the 101st Airborne Brigade that they had

witnessed the killing of several hundred people at Da Mai Creek,

about 10 miles south of Hue, in February of 1968. The area is

wild, unpopulated, virtually inaccessible. The Brigade sent in a

search party, which reported that the stream contained a large

number of human bones.

By piecing together bits of

information, it was determined that this is what happened at Da

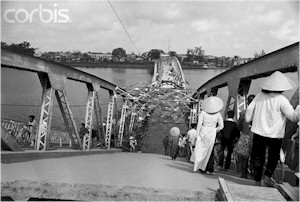

Mai Creek: On the fifth day of Tet in the Phu Cam section of Hue,

where some three–quarters of the City’s 40,000 Roman Catholics

lived, a large number of people had taken sanctuary from the

battle in a local church, a common method in Vietnam of escaping

war. Many in the building were not in fact Catholic.

A Communist political commissar arrived

at the church and ordered out about 400 people, some by name and

some apparently because of their appearance (prosperous looking

and middle–aged businessmen, for example). He said they were

going to the “liberated area” for three days of indoctrination,

after which each could return home.

They were marched nine kilometres south

to a pagoda where the Communists had established a headquarters.

There 20 were called out from the group, assembled before a

drumhead court, tried, found guilty, executed and buried in the

pagoda yard. The remainder were taken across the river and turned

over to a local Communist unit in an exchange that even involved

banding the political commissar a receipt. It is probable that

the commissar intended that their prisoners should be re–educated

and returned, but with the turnover, matters passed from his

control.

established a headquarters.

There 20 were called out from the group, assembled before a

drumhead court, tried, found guilty, executed and buried in the

pagoda yard. The remainder were taken across the river and turned

over to a local Communist unit in an exchange that even involved

banding the political commissar a receipt. It is probable that

the commissar intended that their prisoners should be re–educated

and returned, but with the turnover, matters passed from his

control.

During the next several days, exactly

how many is not known, both captive and captor wandered the

countryside. At some point the local Communists decided to

eliminate witnesses: Their captives were led through six

kilometres of some of the most rugged terrain in Central Vietnam,

to Da Mai Creek. There they were shot or brained and their bodies

left to wash in the running stream. The 101st Airborne Brigade

burial detail found it impossible to reach the creek overland,

roads being non–existent or impassable. The creek’s foliage is

what in Vietnam is called double–canopy, that is, two layers, one

consisting of brush and trees close to the ground, and the second

of tall trees whose branches spread out high above. Beneath is

permanent twilight. Brigade engineers spent two days blasting a

hole through the double–canopy by exploding dynamite dangled on

long wires beneath their hovering helicopters. This cleared a

landing pad for helicopter hearses. Quite clearly this was a spot

where death could be easily hidden even without burial.

captor wandered the

countryside. At some point the local Communists decided to

eliminate witnesses: Their captives were led through six

kilometres of some of the most rugged terrain in Central Vietnam,

to Da Mai Creek. There they were shot or brained and their bodies

left to wash in the running stream. The 101st Airborne Brigade

burial detail found it impossible to reach the creek overland,

roads being non–existent or impassable. The creek’s foliage is

what in Vietnam is called double–canopy, that is, two layers, one

consisting of brush and trees close to the ground, and the second

of tall trees whose branches spread out high above. Beneath is

permanent twilight. Brigade engineers spent two days blasting a

hole through the double–canopy by exploding dynamite dangled on

long wires beneath their hovering helicopters. This cleared a

landing pad for helicopter hearses. Quite clearly this was a spot

where death could be easily hidden even without burial.

The Da Mai Creek bed, for nearly a

hundred yards up the ravine, yielded skulls, skeletons and pieces

of human bones. The dead had been left above ground (for the

animists among them, this meant their souls would wander the

lonely earth forever, since such is the fate of the unburied

dead), and 20 months in the running stream had left bones clean

and white.

Local authorities later released a list of 428 names of

personswhom they said had been positively identified from the

creek bed remains. The Communists’ rationale for their excesses

was elimination of “traitors to the revolution.” The list of 428

victims breaks down as follows: 25 per cent military: two

officers, the rest NCO’s and enlisted men; 25 per cent students;

50 per cent civil servants, village and hamlet officials, service

personnel of various categories, and ordinary workers.

The fourth or Phu Thu Salt Flat Finds

came in November, 1969, near the fishing village of Luong Vien

some ten miles east of Hue, another desolate region. Government

troops early in the month began an intensive effort to clear the

area of remnants of the local Communist organization. People of

Luong Vien, population 700, who had remained silent in the

presence of troops for 20 months apparently felt secure enough

from Communist revenge to break silence and lead officials to the

find. Based on descriptions from villagers whose memories are not

always clear, local officials estimate the number of bodies at

Phu Thu to be at least 300 and possibly 1,000.

The story remains uncompleted. If the

estimates by Hue officials are even approximately correct, nearly

2,000 people are still missing. Re–capitulation of the dead and

missing.

After

the battle, the Goverment of South Viet Nam’s total estimated

civilian casualties resulting from Battle of Hue 7,600:

[1] SEATO: South East Asia

Organization.

–Wounded (hospitalized or outpatients) with injures attributable

to warfare = 1900

–Estimated civilian

deaths due to accident of battle = 844

–First finds–bodies discovered immediately post battle, 1968 =

1173

–Second finds, including Sand Dune

finds, March–July, 1969 (est.) = 809

–Third find, Da Mai Creek find (Nam Hoa district) September, 1969

= 428

–Fourth Finds–Phu Thu Salt Flat

find, November, 1969 (est.) = 300

–Miscellaneous finds during 1969 (approximate) = 200

Total yet unaccounted for = 1946

Total casualty and wounded in Hue

~7,600

[2]

PAVN: People’s Army of Vietnam, soldiers of North Vietnam Army

serving in the South, number currently 105,000.

[3] PLAF: People’s Liberation Armed

Force, Formerly called the National Liberation Front Army.

Communist Rationale

The killing in Hue that added up to the

Hue Massacre far exceeded in numbers any atrocity by the

Communists previously in South Vietnam. The difference was not

only one in degree but one in kind. The character of the terror

that emerges from an examination of Hue is quite distinct from

Communist terror acts elsewhere, frequent or brutal as they may

have been. The terror in Hue was not a morale building act–the

quick blow deep into the enemy’s lair which proves enemy

vulnerability and the guerrilla’s omnipotence and which is quite

different from gunning down civilians in areas under guerrilla

control. Nor was it terror to advertise the cause. Nor to

disorient and psychologically isolate the individual, since the

vast majority of the killings were done secretly. Nor, beyond the

blacklist killings, was it terror to eliminate opposing forces.

Hue did not follow the pattern of terror to provoke governmental

over–response since it resulted in only what might have been

anticipated–government assistance. There were elements of each

objective, true, but none serves to explain the widespread and

diverse pattern of death meted out by the Communists.

atrocity by the

Communists previously in South Vietnam. The difference was not

only one in degree but one in kind. The character of the terror

that emerges from an examination of Hue is quite distinct from

Communist terror acts elsewhere, frequent or brutal as they may

have been. The terror in Hue was not a morale building act–the

quick blow deep into the enemy’s lair which proves enemy

vulnerability and the guerrilla’s omnipotence and which is quite

different from gunning down civilians in areas under guerrilla

control. Nor was it terror to advertise the cause. Nor to

disorient and psychologically isolate the individual, since the

vast majority of the killings were done secretly. Nor, beyond the

blacklist killings, was it terror to eliminate opposing forces.

Hue did not follow the pattern of terror to provoke governmental

over–response since it resulted in only what might have been

anticipated–government assistance. There were elements of each

objective, true, but none serves to explain the widespread and

diverse pattern of death meted out by the Communists.

What is offered here is a hypothesis

which will suggest logic and system behind what appears to be

simple, random slaughter. Before dealing with it, let us consider

three facts which constantly reassert themselves to a Hue visitor

seeking to discover what exactly happened there and, more

importantly, exactly why it happened. All three fly in the face

of common sense and contradict to a degree what has been written.

Yet, in talking to all sources–province chief, police chief,

American advisor, eye witness, captured prisoner, hoi chanh

(defector) or those few who miraculously escaped a death

scene–the three facts emerge again and again.

what appears to be

simple, random slaughter. Before dealing with it, let us consider

three facts which constantly reassert themselves to a Hue visitor

seeking to discover what exactly happened there and, more

importantly, exactly why it happened. All three fly in the face

of common sense and contradict to a degree what has been written.

Yet, in talking to all sources–province chief, police chief,

American advisor, eye witness, captured prisoner, hoi chanh

(defector) or those few who miraculously escaped a death

scene–the three facts emerge again and again.

The first fact, and perhaps the most

important, is that despite contrary appearances virtually no

Communist killing was due to rage, frustration, or panic during

the Communist withdrawal at the end. Such explanations are

frequently heard, but they fail to hold up under scrutiny. Quite

the contrary, to trace back any single killing is to discover

that almost without exception it was the result of a decision

rational and justifiable in the Communist mind. In fact, most

killings were, from the Communist calculation, imperative.

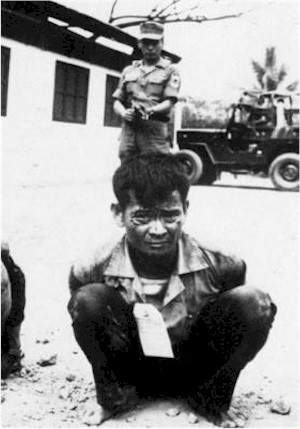

The second fact is that, as far as can

be determined, virtually all killings were done by local

Communist cadres and not by the ARVN troops or Northerners or

other outside Communists. Some 12,000 ARVN troops fought the

battle of Hue and killed civilians in the process but this was

incidental to their military effort. Most of the 150 Communist

civilian cadres operating within the city were local, that is

from the Thua Thien province area. They were the ones who issued

the death orders.

by local

Communist cadres and not by the ARVN troops or Northerners or

other outside Communists. Some 12,000 ARVN troops fought the

battle of Hue and killed civilians in the process but this was

incidental to their military effort. Most of the 150 Communist

civilian cadres operating within the city were local, that is

from the Thua Thien province area. They were the ones who issued

the death orders.

Whether they acted on instructions from

higher headquarters (and the Communist organizational system is

such that one must assume they did), and, if so, what exactly

those orders were, no one yet knows for sure. The third fact is

that beyond “example” executions of prominent “tyrants”, most of

the killings were done secretly with extraordinary effort made to

hide the bodies. Most outsiders have a mental picture of Hue as a

place of public executions and prominent mass burial mounds of

fresh–turned earth. Only in the early days were there

well–publicized executions and these were relatively few. The

burial sites in the city were easily discovered because it is

difficult to create a graveyard in a densely populated area

without someone noticing it. All the other finds were well

hidden, all in terrain lending itself to concealment, probably

the reason the sites were chosen in the first place.

A body in the sand dunes is as

difficult to find as a seashell pushed deep into a sandy beach

over which a wave has washed. Da Mai Creek is in the remotest

part of the province and must have required great exertion by the

Communists to lead their victims there. Had not the three hoi

chanh led searchers to the wild uninhabited spot the bodies might

well remain undiscovered to this day. A visit to all sites leaves

one with the impression that the Communists made a major effort

to hide their deeds. The hypothesis offered here connects and

fixes in time the Communist assessment of their prospects for

staying in Hue with the kind of death order issued. It seems

clear from sifting evidence that they had no single unchanging

assessment with regard to themselves and their future in Hue, but

rather that changing situations during the course of the battle

altered their prospects and their intentions.

sandy beach

over which a wave has washed. Da Mai Creek is in the remotest

part of the province and must have required great exertion by the

Communists to lead their victims there. Had not the three hoi

chanh led searchers to the wild uninhabited spot the bodies might

well remain undiscovered to this day. A visit to all sites leaves

one with the impression that the Communists made a major effort

to hide their deeds. The hypothesis offered here connects and

fixes in time the Communist assessment of their prospects for

staying in Hue with the kind of death order issued. It seems

clear from sifting evidence that they had no single unchanging

assessment with regard to themselves and their future in Hue, but

rather that changing situations during the course of the battle

altered their prospects and their intentions.

It also seems equally clear from the

evidence that there was no single Communist policy on death

orders; instead the kind of death order issued changed during the

course of the battle. The correlation between these two is high

and divides into three phases. The hypothesis therefore is that

as Communist plans during the Battle of Hue changed so did the

nature of the death orders issued. This conclusion is based on

overt Communist statements, testimony by prisoners1 and hoi

chanh, accounts of eyewitnesses, captured documents and the

internal logic of the Communist situation.

Thinking in Phase I was well expressed

in a Communist Party of South Vietnam (PRP) resolution issued to

cadres on the eve of the offensive: Be sure that the liberated

... cities are successfully consolidated. Quickly activate armed

and political units, establish administrative organs at all

echelons, promote (civilian) defence and combat support

activities, get the people to establish an air defence system and

generally motivate them to be ready to act against the enemy when

he counterattacks...”

This was the limited view at the start

– held momentarily. Subsequent developments in Hue were reported

in different terms. Hanoi Radio on February 4 said: “After one

hour’s fighting the Revolutionary Armed Forces occupied the

residence of the puppet provincial governor (in Hue), the prison

and the offices of the puppet administration... The Revolutionary

Armed Forces punished most cruel agents of the enemy and seized

control of the streets... rounded up and punished dozen of cruel

agents and caused the enemy organs of control and oppression to

crumble...

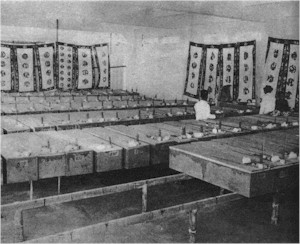

During the brief stay in Hue, the civilian cadres, accompanied by

execution squads, were to round up and execute key individuals

whose elimination would greatly weaken the government’s

administrative apparatus following Communist withdrawal. This was

the blacklist period, the time of the drumhead court. Cadres with

lists of names and addresses on clipboards appeared and called

into kangaroo court various “enemies of the Revolution.”

Their trials were public, usually in

the court–yard of a temporary Communist headquarters. The trials

lasted about ten minutes each and there are no known not–guilty

verdicts. Punishment, invariably execution, was meted out

immediately. Bodies were either hastily buried or turned over to

relatives. Singled out for this treatment were civil servants,

especially those involved in security or police affairs, military

officers and some non–commissioned officers, plus selected

non–official but natural leaders of the community, chiefly

educators and religionists.

With the exception of a particularly

venomous attack on Hue intellectuals, the Phase I pattern was

standard operating procedure for Communists in Vietnam. It was

the sort of thing that had been going on systematically in the

villages for ten years. Permanent blacklists, prepared by zonal

or inter–zone party headquarters have long existed for use

throughout the country, whenever an opportunity presents itself.

However, not all the people named in

the lists used in Hue were liquidated. There were a large number

of people who obviously were listed, who stayed in the city

throughout the battle, but escaped. Throughout the 24–day period

the Communist cadres were busy hunting down persons on their

blacklists, but after a few days their major efforts were turned

into a new channel.

Hue: Phase II

In the first few days, the Tet

offensive affairs progressed so well for the Communists in Hue

(although not to the south, where party chiefs received some

rather grim evaluations from cadres in the midst of the offensive

in the Mekong Delta) that for a brief euphoric moment they

believed they could hold the city. Probably the assessment that

the Communists were in Hue to stay was not shared at the higher

echelons, but it was widespread in Hue and at the Thua Thien

provincial level. One intercepted Communist message, apparently

written on February 2, exhorted cadres in Hue to hold fast,

declaring; “A new era, a real revolutionary period has begun

(because of our Hue victories) and we need only to make swift

assault (in Hue) to secure our target and gain total victory.”

Communists in Hue

(although not to the south, where party chiefs received some

rather grim evaluations from cadres in the midst of the offensive

in the Mekong Delta) that for a brief euphoric moment they

believed they could hold the city. Probably the assessment that

the Communists were in Hue to stay was not shared at the higher

echelons, but it was widespread in Hue and at the Thua Thien

provincial level. One intercepted Communist message, apparently

written on February 2, exhorted cadres in Hue to hold fast,

declaring; “A new era, a real revolutionary period has begun

(because of our Hue victories) and we need only to make swift

assault (in Hue) to secure our target and gain total victory.”

The Hanoi official party newspaper,

Nhan Dan, echoed the theme: “Like a thunderbolt, a general

offensive has been hurled against the U.S. and the puppets... The

U.S.–puppet machine has been duly punished. The puppet

administrative organs... have suddenly collapsed. The Thieu–Ky

administration cannot escape from complete collapse. The puppet

troops have become extremely weak and cannot avoid being

completely exterminated.”

Of course, some of this verbiage is

simply exhortation to the faithful, and, as is always the case in

reading Communist output, it is most difficult to distinguish

between belief and wish. But testimony from prisoners and hoi

chanh, as well as intercepted battle messages, indicate that both

rank and file and cadres believed for a few days they were

permanently in Hue, and they acted accordingly.

Among their acts was to extend the

death order and launch what in effect was a period of social

reconstruction, Communist style. Orders went out, apparently from

the provincial level of the party, to round up what one prisoner

termed “social negatives,” that is, those individuals or members

of groups who represented potential danger or liability in the

new social order. This was quite impersonal, not a blacklist of

names but a blacklist of titles and positions held in the old

society, directed not against people as such but against “social

units.”

period of social

reconstruction, Communist style. Orders went out, apparently from

the provincial level of the party, to round up what one prisoner

termed “social negatives,” that is, those individuals or members

of groups who represented potential danger or liability in the

new social order. This was quite impersonal, not a blacklist of

names but a blacklist of titles and positions held in the old

society, directed not against people as such but against “social

units.”

As

seen earlier in North Vietnam and in Communist China, the

Communists were seeking to break up the local social order by

eliminating leaders and key figures in religious organizations

(Buddhist bonzes, Catholic priests), political parties (four

members of the Central Committee of Vietnam), social movements

such as women’s organizations and youth groups, including what

otherwise would be totally inexplicable, the execution of

pro–Communist student leaders from middle and upper class

families.

In

consonance with this, killing in some instances was done by

family unit. In one well–documented case during this period a

squad with a death order entered the home of a prominent

community leader and shot him, his wife, his married son and

daughter–in–law, his young unmarried daughter, a male and female

servant and their baby. The family cat was strangled; the family

dog was clubbed to death; the goldfish scooped out of the

fish–bowl and tossed on the floor. When the Communists left, no

life remained in the house. A “social unit” had been eliminated.

Phase II also saw an intensive effort

to eliminate intellectuals, who are perhaps more numerous in Hue

than elsewhere in Vietnam. Surviving Hue intellectuals explain

this in terms of a long–standing Communist hatred of Hue

intellectuals, who were anti–Communist in the worst or most

insulting manner: they refused to take Communism seriously. Hue

intellectuals have always been contemptuous of Communist

ideology, brushing it aside as a latecomer to the history of

ideas and not a very significant one at that. Hue, being a

bastion of traditionalism, with its intellectuals steeped in

Confucian learning intertwined with Buddhism, did not, even in

the fermenting years of the 1920s, and 1930s, debate the merits

of Communism. Hue ignored it. The intellectuals in the

university, for example, in a year’s course in political thought

dispense with Marxism–Leninism in a half hour lecture, painting

it as a set of shallow barbarian political slogans with none of

the depth and time–tested reality of Confucian learning, nor any

of the splendor and soaring humanism of Buddhist thought.

Since the Communist, especially the

Communist from Hue, takes his dogma seriously, he can become

demoniac when dismissed by a Confucian as a philosophic

ignoramus, or by a Buddhist as a trivial materialist. Or, worse

than being dismissed, ignored through the years. So with the

righteousness of a true believer, he sought to strike back and

eliminate this challenge of indifference. Hue intellectuals now

say the hunt–down in their ranks has taught them a hard lesson,

to take Communism seriously, if not as an idea, at least as a

force loose in their world.

seriously, he can become

demoniac when dismissed by a Confucian as a philosophic

ignoramus, or by a Buddhist as a trivial materialist. Or, worse

than being dismissed, ignored through the years. So with the

righteousness of a true believer, he sought to strike back and

eliminate this challenge of indifference. Hue intellectuals now

say the hunt–down in their ranks has taught them a hard lesson,

to take Communism seriously, if not as an idea, at least as a

force loose in their world.

The killings in Phase II perhaps

accounted for 2,000 of the missing. But the worst was not yet

over.

Hue:

Phase III

Inevitably, and as the leadership in Hanoi must have assumed all

along, considering the forces ranged against it, the battle in

Hue turned against the Communists. An intercepted PAVN radio

message from the Citadel, February 22, asked for permission to

withdraw. Back came the reply: permission refused, attack on the

23rd. That attack was made, a last, futile one. On the 24th the

Citadel was taken.

That expulsion was inevitable was

apparent to the Communists for at least the preceding week. It

was then that Phase III began, the cover–the–traces period.

Probably the entire civilian underground apparat in Hue had

exposed itself during Phase II. Those without suspicion rose to

proclaim their identity. Typical is the case of one Hue resident

who described his surprise on learning that his next door

neighbor was the leader of a phuong (which made him 10th to 15th

ranking Communist civilian in the city), saying in wonder, “I’d

known him for 18 years and never thought he was the least

interested in politics.” Such a cadre could not go underground

again unless there was no one around who remembered him.

Hence Phase III, elimination of

witnesses. Probably the largest number of killings came during

this period and for this reason. Those taken for political

indoctrination probably were slated to be returned. But they were

local people as were their captors; names and faces were

familiar. So, as the end approached they became not just a burden

but a positive danger. Such undoubtedly was the case with the

group taken from the church at Phu Cam. Or of the 15 high school

students whose bodies were found as part of the Phu Thu Salt Flat

find.

Categorization in a hypothesis such as this is, of course, gross

and at best only illustrative. Things are not that neat in real

life. For example, throughout the entire time the blacklist hunt

went on. Also, there was revenge killing by the Communists in the

name of the party, the so–called “revolutionary justice.” And

undoubtedly there were personal vendettas, old scores settled by

individual party members.

The official Communist view of the

killing in Hue was contained in a book written and published in

Hanoi: “Actively combining their efforts with those of the PLAF

and population, other self–defence and armed units of the city

(of Hue) arrested and called to surrender the surviving

functionaries of the puppet administration and officers and men

of the puppet army who were skulking. Die–hard cruel agents were

punished.”

The

Communist line on the Hue killings later at the Paris talks was

that it was not the work of Communists but of “dissident local

political parties”. However, it should be noted that Hanoi’s

Liberation Radio April 26, 1968, criticized the effort in Hue to

recover bodies, saying the victims were only “hooligan lackeys

who had incurred blood debts of the Hue compatriots and who were

annihilated by the Southern armed forces and people in early

Spring.” This propaganda line however was soon dropped in favour

of the line that it really was local political groups fighting

each other.

(An

Excerpt from the Viet Cong Strategy of Terror, Douglas Pike)

With sincere gratitude, we are paying respect to the late

Professor/Author Douglas Eugene Pike of Texas Tech University.

http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/vietnamcenter/general/douglas_pike.htm

Bấm vào đây để in ra giấy (Print)

Những

bài liên hệ

Trang

chính

Bài 1:

Đại Cương Tiểu Sử & Vài Nét Hoạt Động

của Nha Kỹ Thuật/Bộ Tổng Tham Mưu–QLVNCH

Bài 2:

Huyền Thoại Nhưng Có Thật

Bài 3:

Vài nét về Biệt Kích Dù hoạt động ngoài Bắc Việt

Bài 4:

Sự Hình thành & Hoạt động của Sở Phòng Vệ Duyên Hải/Nha Kỹ Thuật, BTTM QLVNCH

Bài 5:

Mặt Trận Gươm Thiêng Ái Quốc & Thiên Ðàng Ðảo

Bài 6:

Phi Công Phan Thanh Vân

Bài 7:

Anh Hùng Biệt Hải

– Anh Là Ai?

Bài 8:

Tự Truyện một Phi Công

Bài 9:

Người Việt, Anh hay Chị ở vị trí nào?

Bài 10:

50 năm tưởng niệm Tết Mậu Thân

Bài 11:

Trả lại Sự Thật cho Lịch sử

Bài 12:

Bài thơ LÔI HỔ

Bài 13:

Tâm sự Người ở lại

Bài 14:

Hành quân phá hủy Mật khu Vũng Rô

– Hồi ký NN Lê Đình An

Bài 15:

Bài thơ CHIẾN THẮNG VŨNG RÔ

Bài 16:

Mình 3 đứa

Bài 17:

Sở Liên Lạc và Tôi

Bài 18:

Tóm lược sự Hình thành Nha Kỹ Thuật

Bài 19:

Phi Đoàn 219 KINGBEE

Bài 20:

Người Lính & những Người Lính

Bài 21:

Lính Biệt Kích

– Bóng Ma và Ma Ám

Bài 22:

Toán Chiêu Hồi

Bài 23:

Bóng Ma Biên Giới

THIÊN SỨ MICAE – BỔN MẠNG SĐND VNCH

|

|

Hình nền: thắng cảnh đẹp thiên nhiên hùng vĩ. Để xem được trang web này một cách hoàn hảo, máy của bạn cần được trang bị chương trình Microsoft Internet Explorer (MSIE) Ấn bản 9 hay cao hơn hoặc những chương trình Web Browsers làm việc được với HTML–5 hay cao hơn.

Nguồn: Internet eMail by Đoàn Hữu Định chuyển

Đăng ngày Thứ Hai, June 11, 2018

Ban Kỹ Thuật

Khóa 10A–72/SQTB/ĐĐ, ĐĐ11/TĐ1ND, QLVNCH

GĐMĐVN/Chi Hội Hoa Thịnh Đốn & Phụ cận

P.O.Box 5345 Springfield, Virginia, VA 22150

Điện thoại & Điện thư:

Liên lạc

Trở lại đầu trang